a guide to

Graceland Cemetery

Planning a visit?

Check out these resources:

“THE CEMETERY OF ARCHITECTS”

Header photo by Shutterstock/Carlos Yudica. Information & other photos are credited to Graceland Cemetery.

Graceland Cemetery was established in 1860 by attorney Thomas Bryan, who hired prominent landscape architect H.W.S. Cleveland to plan its park-like ambiance. With Bryan as president of the cemetery company, many prominent Chicagoans joined the board of managers, including the city’s first mayor, real estate entrepreneur William Ogden. Many other wealthy Chicagoans became members and purchased large family lots and “landscape rooms.” Still an active cemetery at 119 acres, even today Graceland can accommodate a few more Chicago families who want to join this prominent pantheon.

Long famous as the “Cemetery of Architects,” Graceland Cemetery even owes its design and exceptional natural beauty to two 19th century landscape architects. It began with a plan by landscape architect Cleveland, which, in the 1870’s, saw the cemetery’s paths and plots uniformly sodded, and the fenced and curbed plot boundaries eliminated. William Le Baron Jenney, a renowned architect but less well known for his landscape work, contributed significantly with his design and engineering input. This helped created the Victorian park style atmosphere that soon was enhanced by Ossian Simonds. When Graceland grew to its present size, Simonds innovative design used native plants to create the cemetery’s pastoral landscape, which today makes it one of the most beautiful places in Chicago for residents and tourists to visit.

Today, Graceland is owned and operated by the Trustees of the Graceland Cemetery Improvement Fund, a not-for-profit trust. Revenues provide for maintenance of the grounds and the monuments and tombs therein. The Cemetery is open to all to visit, and its architectural masterpieces, local history and beauty are the magnets that attract people to Graceland. While architects from the traditional to the father of skyscrapers and modern masters take center stage, you’ll find that Graceland also holds fascinating stories of private eyes and public figures, baseball and boxing greats, merchants and inventors and other unique individuals.

The Architects

Graceland Cemetery is the premiere resting place – and showplace – for a “who’s who” of Chicago’s most outstanding architects. From the original designers of Graceland, landscape architects H.W.S. Cleveland and Ossian Simonds, partners Holabird and Roche, who designed the Cemetery’s buildings, to William Le Baron Jenney, the father of the skyscraper, the great Louis Sullivan and right up to modern masters like Mies van der Rohe and Khan, their influence on commercial and residential spaces spans centuries past, through the present and likely long into the future. Graceland Cemetery is proud to pay homage to Chicago’s great architects with examples of their work and summaries of their lives.

Louis Sullivan, 1856 -1924

For the man whose designs and writings helped create modern architecture, you have to look somewhere other than Sullivan’s Graceland resting place for monuments to his own life. While Sullivan designed two tombs for others in Graceland, his own simple, rough-hewn headstone at his parent’s gravesite belies his great contributions as the “Father of the Chicago School of Architecture.” An outstanding example of his work still stands in Chicago – the Carson Pirie Scott store, one of the few Sullivan buildings that remain in the Loop.

John Root, 1850 –1891

Root, one of the founders of the leading Chicago Architecture firm of Burnham and Root, is one of the fathers of the Chicago “school” of architecture. Although Root spent his career breaking away from architectural tradition, members of his firm created a totally traditional Celtic cross, which Root had admired in English cemeteries. Charles Atwood chose a Druid style, and Jules Wegman provided the design, which includes one of Root’s drawings, the entrance to the Phoenix Building, which did not rise from its own ashes when it was demolished in 1959.

Chicago's Underground Railroad

An estimated 3,000 to 4,500 persons escaping enslavement used Chicago's Underground Railroad. For most, it was a stepstone to freedom in Canada, and for others, it became home. Graceland Cemetery is the resting place of at least 29 activists who helped them.

The earliest arrivals came to Chicago in the 1830s. By 1860, Chicago was known downstate as "a hotbed" of abolitionism.

Why Chicago? Its location on Lake Michigan was the main reason. Many of those bound for Canada boarded a steam-powered boat at the lakeshore and got off at Detroit, where freedom lay on the other side of a river.

Another reason was the activism of the City's free Black population. Newspaper accounts tell of streets, docks, and courtrooms packed with people enraged by an arrest, or by a slave-catcher or kidnapper on the prowl. White abolitionists joined them and received most of the publicity from the white-owned press.

In 2021, Graceland Cemetery was added to the National Park Service's Network to Freedom in recognition of the Underground Railroad activists buried here.

Underground Railroad Activists at Graceland

There are 29 known UGRR activists buried at Graceland:

Isaac Newton Arnold was a politician, attorney, and biographer born in New York State. He defended people arrested for sheltering escapees from slavery, but perhaps his biggest impact on Chicago's UGRR was as a member of the Illinois legislature, where he helped arrange funding for the Illinois and Michigan Canal. Completed in 1848, the Canal made transportation to Chicago much easier from downstate.

Emma Jane Gordon Atkinson was almost certainly one of the "Big Four," four legendary Black women who led Quinn Chapel's Underground Railroad operations. She was born in Connecticut, her husband Isaac Atkinson in Virginia, each had a parent who was Cherokee. Isaac ran a successful omnibus line (horse-drawn wagons) and then worked for the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad.

Ailey Maria Richardson Bradford was born in Tennessee, her husband Henry Bradford in Virginia. Henry was a barber and helped Black Chicagoans flee to Canada after the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law was passed. During the Civil War, Henry helped support "contrabands," people who had been freed by the Union Army. Ailey was the older sister of Mary Richardson Jones and helped needy families.

Philo Carpenter, born in Massachusetts, was Chicago's first pharmacist. He and his wife Ann Thompson Carpenter treated cholera patients at the risk of their own lives. They sheltered an estimated 200 freedom seekers in their home and Philo's shop. Chicago's Carpenter Street and a school are named for Philo, and Racine Avenue was originally named Ann Street in honor of Ann.

James H. Collins became known as the attorney you wanted if you were arrested for sheltering freedom seekers. Born in New York State, he formed legal partnerships with several distinguished lawyers who are buried at Graceland, including Justin Butterfield. His wife Olive Spencer Collins was active in the anti-slavery society for women in Illinois.

L. C. Paine Freer was born in New York State and studied law with James H. Collins. He was known to chase slave-catchers on horseback and helped John Jones free a man. With his wife Esther Wickes Marble Freer, he dined with the Joneses at a time when interracial socializing was extremely rare.

Charles Goodrich Hammond, born in Connecticut, was famous as a railroad man and reportedly concealed freedom seekers on special baggage cars. In 1859, Hammond helped Allan Pinkerton make arrangements for John Brown and his party to reach Detroit by train.

Joseph Henry Hudlun was born enslaved in Virginia, and in Chicago, he married Anna Elizabeth Lewis Hudlun, born in Pennsylvania to a freed mother. The couple were active members of Quinn Chapel and sheltered freedom seekers in their home near Dearborn Station. They became community heroes after the Great Chicago Fire for opening their doors to homeless families and for Joseph's rescue of documents at the Chicago Board of Trade where he worked as custodian. Joseph is buried at Graceland, Anna at Mount Greenwood, each with some of their many children.

John Jones was born free in North Carolina but was at risk of enslavement numerous times. He married Mary Richardson Jones from Memphis, Tennessee. Trained as a tailor, John became both a successful businessman and the leader of Chicago's Black community. He helped run an agency that helped Black Chicagoans find jobs, homes, and loans. John and Mary sheltered escapees in their home and also hosted Frederick Douglass and John Brown.

Edwin Channing Larned was an attorney and orator, born in Rhode Island. With George Manierre, he helped defend Moses Johnson, a free Black man who had been wrongly arrested, and he later served on the defense team in the Ottawa Rescue Case. President Lincoln appointed him U.S. District Attorney for the Northern District of Illinois, where he dismissed indictments against people who had helped freedom seekers escape.

George Manierre was an admired and beloved judge. Born in Connecticut, he served in a variety of elected positions, and he and his wife, Ann Hamilton Reid Manierre, sheltered freedom seekers in their home. With Edwin Channing Larned he helped defend Moses Johnson. The Manierres lost two young children who were buried in Chicago's City Cemetery, located where Lincoln Park is today, and their activism for better conditions there helped lead to the early success of Graceland Cemetery.

Mahlon Dickerson Ogden was a successful businessman. He freed a Black man who had been auctioned off by the Sheriff for not having freedom papers. Ogden was born in New York, and his brother William was the first Mayor of Chicago.

Seth Paine was an eccentric idealist who worked as a merchant, banker, minister, social reformer, and Union spy. Born in Vermont, he came to Chicago around 1834 and founded Lake Zurich, where he and his first wife sheltered freedom seekers. During the Civil War, he was one of Allan Pinkerton's best agents behind enemy lines.

Allan Pinkerton is perhaps the most famous of Graceland's UGRR activists. Born in Scotland, he married singer Joan Carfrae Pinkerton, and the couple moved soon afterward to North America. They settled in suburban Dundee where they sheltered freedom seekers, and Allan taught them his trade of barrel-making. He became a detective and the family moved to Chicago, where they continued to shelter people.

Rev. Joseph Edwin Roy was born in Ohio in a log cabin. He and his wife Emily Stearns Hatch Roy first sheltered a freedom seeker in Peoria in 1854. In Chicago, Joseph became an outspoken pastor, and in 1859 he held a prayer meeting on the day John Brown was executed. In 1861 the Roys hid a woman from a US Marshall in their hotel room for two days.

Julius Alphonzo Willard was born in Connecticut and married Almyra Cady Willard from Massachusetts. In the Jacksonville, Illinois, area, they got involved in the UGRR. In 1843, Julius and their son, Samuel Willard, while a college student, were arrested, convicted, and fined for trying to help a woman escape from her mistress. They were posthumously exonerated by Illinois Governor Pat Quinn in 2014. Samuel married Harriet Jane Edgar Willard, and both Willard families continued to shelter freedom seekers.

John McNeil Wilson was born in New Hampshire and in Chicago became a respected judge. He assisted the legal teams for several famous defendants charged under the Fugitive Slave Act and donated money to help John Brown and his party to reach Detroit by train.

Stories of the Underground Railroad involving Graceland Activists

1842: A man from Downer's Grove stopped at the home of Philo and Ann Carpenter on the way to see his son in Chicago, with four freedom seekers hidden in his wagon. The Carpenters sheltered and fed them and put them on a boat for Canada the next day. Another time, the Carpenters sheltered a husband and wife brought to them from Kane County. Ann was worried that their house was being watched. With the help of Black activists and a band of armed men, the couple was driven to the lakeside in a covered wagon and put on board a lumber boat.

1842: A Black laborer named Edwin Heathcock was accused by a white man of not having freedom papers. The sheriff arrested him and advertised that he would be auctioned off to pay court costs. Activists posted a flyer with the day and time of the auction up and down Clark Street. When the time came, an angry crowd refused to place bids. Then businessman Mahon Dickerson Ogden bid 25 cents, handed the sheriff a quarter, and told Heathcock he was free. Twenty years later Heathcock joined the Union Army.

1843: Julius Alphonzo Willard and his son Samuel Willard were arrested, convicted, and fined for trying to help a woman escape. In 2014 they were posthumously exonerated.

1843: Abolitionist Owen Lovejoy was acquitted in 1843 for sheltering two women with help from attorney James H. Collins. Before returning to Chicago, Collins volunteered to defend a church deacon on a similar charge, with John M. Wilson assisting, but charges were dropped when those pressing the complaint felt ashamed about proceeding.

1845: John and Mary Jones took in three girls who had arrived from Missouri in a wagon covered in straw. The girls stayed until spring and were then sent on to Canada. One of them later returned to Chicago, and one of her daughters lived with the Joneses for five years and became a teacher.

1846: Three free Black men were falsely accused of being escapees from Missouri. A huge crowd surrounded the courtroom where James H. Collins and L. C. Paine Freer were to defend them. The crowd rushed the door, and the men used the commotion to get away.

1846-47: Quinn Chapel, Chicago's first A.M.E. congregation, opened its doors at Jackson and Dearborn and became a hub of UGRR activity because of work by activists like Emma Jane Gordon Atkinson and Isaac Atkinson.

1850: Xenia Baptist Church (later named Olivet) formed at Buffalo and Taylor Streets, and its members included some of the most active UGRR activists, including John and Mary Jones, and Henry and Ailey Bradford.

1850: After Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law, a large crowd led by John Jones and Henry Bradford gathered at Quinn Chapel. The community formed a Vigilance Committee to patrol the streets every night on the lookout for slave-catchers and asked white Chicagoans to assist them.

1851: John Jones, Henry Bradford, and others organized a Freemasons Lodge called the North Star Lodge. It probably helped them communicate with similar lodges in other states about freedom seekers heading north. Joseph H. Hudlun was also a member.

1851: Moses Johnson was the first Chicagoan charged under the new Fugitive Slave Law, and thousands filled the streets to protest. George Manierre, Edwin Channing Larned, L. C. Paine Freer, and John M. Wilson were on the defense team. Johnson was acquitted when it became clear that his appearance didn't match the pursuer's description. The crowd hurried Johnson to safety. Chicago historian A. T. Andreas wrote that if the decision had gone the other way, Johnson would still have escaped because the Underground Railroad was so active in the City.

1852: John Jones and L. C. Paine Freer helped free a man named Albert Pettit who had escaped from Tennessee. In order to satisfy Pettit's former enslaver, they raised a large amount of money from the community, and Freer drew up a legal document to prove Pettit's freedom.

1850s: The pace of freedom seekers arriving sped up, sometimes dozens per day, hundreds per week, thanks to improved transportation.

1857: A white farmer brought his Black teenage ward to Chicago on their way to his home southwest of the City. A false rumor spread that the boy was going to be sold, and the streets filled with angry citizens. After investigating, Allan Pinkerton begged the crowd to let them continue, but they refused to listen, not knowing he was a UGRR activist. He used a subterfuge to help the two go on their way.

1859: Abolitionist John Brown stopped in Chicago with his sons, helpers, and 12 freedom seekers from Missouri. The white men stayed in the home of John and Mary Jones, where they were visited by attorneys James H. Collins and L. C. Paine Freer. The freedom seekers were hidden in a mill while Allan Pinkerton arranged with Charles G. Hammond for their transportation by train to Detroit. Pinkerton raised money for their train fare from John M. Wilson and George Manierre among others.

1859-1860: Three white abolitionists helped a man named Jim Gray escape from a courtroom in Ottawa, Illinois. Gray reached Chicago, where Philo Carpenter sent him on to Canada. The three men were arrested and tried in Chicago, where they were defended by Isaac N. Arnold and Edwin Channing Larned. Only one of them served jail time, and Chicagoans, including the Mayor, treated him like a hero with "days of banqueting."

1861: Emily Stearns Hatch Roy and her husband, Rev. Joseph Edwin Roy, were living in a hotel on State Street. The hotel cook had purchased his freedom, and his wife worked in the hotel laundry. A US Marshal came to take her into custody, and Emily hid her in a large closet and put a desk in front of the door. While Emily sat calmly sewing, the Marshal's bloodhound tracked the woman to the desk, but the Marshal couldn't see a hiding place and left. The Roys hid the woman until they could get her out of Chicago.

1861: Seth Paine became a Union spy during the Civil War, working for Allan Pinkerton, who considered him one of his best agents behind enemy lines.

Daniel Burnham, 1846 - 1912

Burnham, a partner of John Root, became known for his dictum, “Make no little plans.” And indeed, he practiced what he preached. He was chief of construction for the 1893 Columbian Exposition, and his Chicago Plan of 1909 is the reason that Chicago’s lakefront has been preserved for the enjoyment and recreational use of its citizens and tourists.So it seems fitting that his final resting place is on a pleasant, wooded isle in the lake at Graceland.

Howard Van Doren Shaw, 1868 - 1926

The designer of the Goodman lakeside mausoleum, Shaw was a contemporary of Frank Lloyd Wright and others of the Prairie School of Architecture, but not one of the group. His designs remained traditional, which made him a favorite of wealthy residents of Lake Forest and other North Shore communities, for whom he designed many country homes. The bronze ball on top of the elegant granite pillar contains the words of the 23rd Psalm.

Richard Nickel, 1928 – 1972

Nickel was an architectural photographer who met his untimely death by trying to salvage bits of Adler & Sullivan’s Stock Exchange on LaSalle Street before it was demolished. His body was found in the rubble weeks after his disappearance. The artifacts he collected and his photographs are about all that’s left of many of the Adler & Sullivan buildings that once graced the Loop.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, 1886 -1969

Said – and meant – “less is more.” Leader of the International Style. Spent his life perfecting the “universal” building – bones of steel, skin of glass. See the Federal Center in the Loop. His most appropriate black granite marker was designed by his grandson, architect Dirk Lohan.

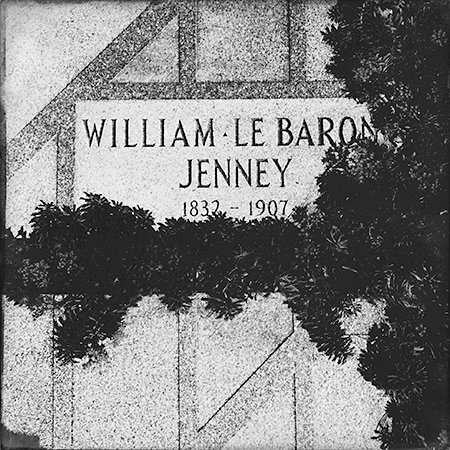

William Le Baron Jenney, 1832 - 1907

Known as the “Father of the Skyscraper,” Jenney studied engineering and architecture at Harvard and in Paris, where he graduated one year after Gustave Eiffel. Jenney served as Grant’s and Sherman’s engineer during the Civil War, rising to the rank of Major, then moved to Chicago in 1867. He designed the first fully metal-framed skyscraper, the Home Insurance Building, built in 1885, four years before Eiffel’s more famous tower. Although Jenney’s creation was demolished in 1931, his heritage lives on through the apprentices he mentored, and who became leading architects in their own right, including Louis Sullivan, Daniel Burnham, William Holabird and Martin Roche. When Jenney died, in 1907, his ashes were scattered over his wife’s grave at Graceland. (Note: It’s no longer allowed). One hundred years later, his memory was properly honored with a new gravestone, dedicated in June of 2007.

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, 1895 - 1946

Moholy-Nagy attended the Bauhaus, a new kind of school of architecture, art, and design, from 1923-1928. He was able to incorporate the methods and exercises he learned while attending the Bauhaus into his own school, The School of Design in Chicago, which opened February 1939. He aimed at educating the whole person and he placed emphasis on teamwork and experimentation. In 1944, the school was reorganized and renamed The Institute of Design in Chicago. In 1949, the school became a department of the Illinois Institute of Technology, where it continues today, a direct descendant of Moholy-Nagy's school. Moholy-Nagy was an accomplished artist in many fields including painting, sculpting, photography and film.

Fazlur Khan, 1929 – 1982

Khan has his most impressive monument in downtown Chicago: the 110-story Sears Tower. It’s there that his “tube” theories – framed, trussed and bundled – literally reached their highest point, and where his most famous quote is engraved on a plaque – “The technical man must not be lost in his own technology. He must be able to appreciate life; and life is art, drama, music, and most importantly, people.” His other masterworks include Chicago’s 43-story Dewitt-Chestnut Apartments and 100-story John Hancock Center.

Marion Mahony Griffin, 1871 - 1971

Marion Mahony Griffin became the first licensed female architect in the U.S. and the only woman in the Oak Park Studio of Frank Lloyd Wright. Some claim she was the real talent behind the Prairie School for which Wright is given credit. Her drawings helped her husband, Walter Burley Griffin win an international competition to design Australia’s new capital, Canberra. In Australia, India and America, she and her husband implemented their belief that “beyond blending beauty and function, buildings should be ecologically sound… They should provide an environment enhancing the physical, psychological and spiritual well-being of the people who work in them.” Her remains have been moved from an unmarked grave to a columbarium with a plaque featuring her name and one of her flower drawings.

Dwight Heald Perkins, 1867 -1941

Perkins established his architectural practice in Chicago in 1894 with a commission from the Steinway Piano Company to design a building. He invited some friends to share the office space, and thus Steinway Hall and the Prairie School of Architecture had their beginnings. His respect for natural materials and eliminating excess details in his designs were hallmarks of the Prairie School. Acknowledged as a pioneering architect, throughout the 1910s and the early 1920s he specialized in schools, utilizing the social agenda and the aesthetics of the Arts and Crafts movement. Perkins incorporated the functional style of the architecture known as the Chicago School into many of his designs. His designs included Albert Lane Technical High School (1908, ¬1910), Carl Schurz High School (1908, ¬1910), and the Lion House (1912) at Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo. Perkins’ participation in preserving open space helped to establish the Cook County Forest Preserve. He is buried in the family lot along with other family members, including his son Lawrence Bradford Perkins, also a noted Chicago architect, who founded the architectural firm of Perkins & Will in 1935.

Bruce Goff, 1904 -1982

Bruce Goff became an architectural apprentice at the age of twelve. Self-educated, he employed creative free association and borrowed materials in his designs. In his private practice, while remaining sensitive to the needs of the client and the constraints of the site, Goff integrated exposed structure and spatial complexity with a degree of enhancing details. This technique was known as organic architecture; a development of concepts started by his mentor, Frank Lloyd Wright. It was this attention to detail that set him apart as an architect and why he is regarded as one of the masters of organic architecture.

Monuments and their Makers

Another tribute to Chicago’s great schools of architecture can be seen in Graceland Cemetery’s monuments to some of Chicago’s leading lights. So many prominent people left behind impressive memorials, designed by leading architects and decorated by famous sculptors, that architectural tours through Graceland are enjoyed by thousands throughout the year. The Chicago Architecture Foundation has published a book for a self-guided tour, titled “A Walk through Graceland Cemetery,” which you can purchase from the Graceland office or directly from the Foundation.

Graceland is indebted to the Foundation for many of the descriptions here. For more detailed architectural information about Graceland and Chicago’s architecture, we recommend you visit their website.

Dexter Graves, 1789 - 1844

Graves was one of the first settlers who, according to the inscription on the back of the polished black granite slab, “brought the first colony to Chicago, consisting of 13 families, arriving here July 15, 1831 from Ashtabula, Ohio, on the schooner Telegraph.”

The bronze figure, “Eternal Silence,” was created in 1909 by sculptor Lorado Taft, whose monumental “Fountain of Time” stands at the west end of the University of Chicago Midway.

Peter Schoenhofen, 1827 - 1893

Wealthy brewer Schoenhofen’s pyramid was designed by architect Richard Schmidt in 1893. It features the unlikely combination of an Egyptian pyramid and sphinx with a typical Victorian era angel. Since that may be hedging one’s bet on the afterlife, we say: Prosit, Herr Schoenhofen. (Literal translation of this German toast: “May it be useful, Mr. Schoenhofen.”)

William Goodman, 1848 -1936

Goodman, another Chicago lumber magnate, had this impressive lakeside mausoleum built for his son Kenneth, a naval lieutenant in training who was a victim of the 1918 influenza epidemic. The elder Goodman’s friend, architect Howard Van Doren Shaw, designed it, using the same neoclassical style he would use in 1925 for the Goodman Theatre, which was founded as a memorial to the Goodmans’ dramatist son.

Potter Palmer, 1826 - 1902 & Bertha Palmer, 1849 - 1918

The grand Greek temple with the twin sarcophagi gives a clue to the lavish lifestyle of its occupants. Potter Palmer pioneered customer satisfaction in his dry goods store, with money-back guarantees, merchandise on approval, and attractive store displays. He sold his successful business to Marshall Field and Levi Leiter, and became successful in real estate. (You’ve heard of the Palmer House, no doubt.) McKim, Mead & White of New York designed the temple, as well as Bertha’s parents' French Gothic tomb across the road.

Getty Tomb

Considered the piece de resistance of all the fine monuments in Graceland, this masterpiece was commissioned by lumber merchant Henry Harrison Getty for his wife, Carrie Eliza. Designed by Louis Sullivan, it’s a delicately ornamented cube uniquely suited to its purpose as a woman’s last resting place. It was designated a city landmark in 1971, by the Commission on Chicago Historical and Architectural Landmarks. Their inscription on the plaque in front explains the building’s significance: “The Getty Tomb marks the maturity of Sullivan’s architectural style and the beginning of modern architecture in America. Here the architect departed from historic precedent to create a building of strong geometric massing, detailed with original ornament."

Marshall Field, 1835 -1906

This giant of commerce is commemorated in a memorial created in by the two men who later would be responsible for the Lincoln Memorial – architect Henry Bacon & sculptor Daniel Chester French. Field, who went from store clerk to Chicago’s richest man, developed his famous company into the world’s largest wholesale and retail dry goods enterprise. French’s statue, the sad-faced woman titled “Memory,” holds oak leaves, a symbol of calm courage. The caduceus on the base, the staff of Mercury, is used today mostly to represent medicine. But we are told that here, it stands for commerce. Mercury was the classical god of commerce – as well as of skill, eloquence, cleverness, travel and thievery.

Martin Ryerson, 1818 - 1887

Of the three tombs design by famed Chicago architect Louis Sullivan, two are in Graceland. This, the Martin Ryerson Mastaba and Pyramid, was the first. Ryerson made two fortunes -- in lumber and real estate -- in the second half of the 19th century. Sullivan and his partner Dankmar Adler had designed four Ryerson buildings, and son Martin A. Ryerson turned to Sullivan for this unique black granite tomb, which combines two Egyptian burial monument styles into one massive, time-defying memorial.

Public Figures and Private Eyes

The graves of many who are a part of Chicago’s history can be found at Graceland. The famous - and infamous - politicians, civic leaders and even America’s most famous private detective and the first female detective.

Charles Wacker, 1856 – 1929, is the man for whom Wacker Drive is named, thanks to his position as chairman of the Chicago Plan Commission, which gained public acceptance of Daniel Burnham’s Chicago Plan of 1909.

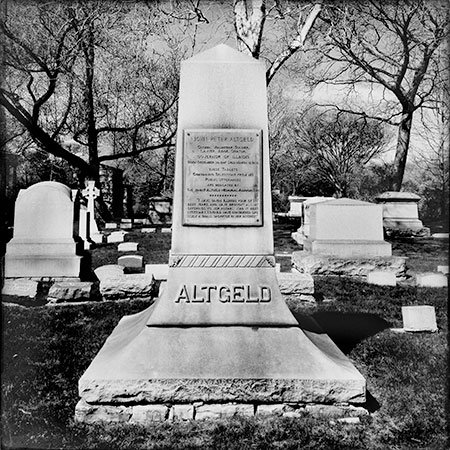

John Peter Altgeld, 1847 – 1902, was a lawyer, judge, author of a book on prison reform and governor of Illinois from 1893 to 1897. But he’s most famous – or infamous – for two decisions – his 1893 pardon for three imprisoned Haymarket Riot anarchists and his protest against sending Federal troops to quell the Pullman strike in 1894.

Allan Pinkerton, 1819 – 1884, came to America from Scotland. Working as a cooper in Ohio, he discovered the hideout of a gang of counterfeiters, helped nab the gang, and became a deputy sheriff. His reputation spread, he became Cook County Sheriff, then Chicago’s first detective. When he went private, his trademark was the unblinking eye. He was also an ardent abolitionist, and part of the Underground Railroad.

A memorial stone for Timothy Webster (buried in Onarga, Illinois) is next to Kate Warn who is buried near Pinkerton, their employer. Kate, the nation’s first female private eye, and Timothy helped Pinkerton escort Abraham Lincoln to his inauguration. Webster, in Pinkerton’s secret service, was hanged by the Confederacy as a spy during the Civil War.

Joseph Medill, 1823 – 1899, and his newspaper, the Chicago Tribune, were staunchly conservative, Republican, anti-slavery and anti-labor union. After the Chicago Fire, he was elected Mayor on the “fireproof” ticket, established the Chicago Library and closed the saloons on Sunday. That last act was enough to get him to resign before his term was up and go to Europe for a rest. The law was repealed. He returned in 1874 and took full control of the Tribune.

John Jones, 1816 – 1879, was the first black man to hold elective office in Chicago. Born in North Carolina of a free woman and a German named Bromfield, his mother apprenticed him to a tailor. He built a successful business as a tailor in Chicago, and because of the city’s restrictive laws, he taught himself to read and write, aided fugitive slaves and worked to change the law regarding blacks. He served two terms as a county commissioner after the Fire.

Fred Busse, 1886 – 1914, is one of dozens of politicians entombed at Graceland. After a term as Illinois State Treasurer from 1903 to 1905, he became the 32nd mayor of the Chicago, serving from 1907 to 1911. Some claim he served himself most of all, allowing for widespread corruption and organized crime during his mayoralty.

Carter Harrison Sr., 1825 – 1893, came north from Kentucky because of his disdain for slavery. A lawyer, he made money in real estate, and was first elected mayor of Chicago in 1879. Calling Chicago “a free town,” he allowed brothels and gambling in one section of the city, and encouraged ethnic neighborhood saloons.

Popular until the Haymarket Riot, he was voted out of office, but elected to a non-consecutive fifth term in time for the Columbian Exposition, and was assassinated just before it concluded. Tens of thousands followed his casket to Graceland Cemetery and 500,000 other Chicagoans lined the streets to watch. He bought the Chicago Times in 1891.

Carter Harrison, Jr. 1860 – 1953, like his father, was elected mayor of Chicago five times. He served from 1897 to 1905, and again from 1911 to 1915. The 30th mayor, he was the first one to be born in the city. Although similar to his father in not legislating morality, he was more of a reformer, which helped him earn the support of the middle class. But there is no report of the same size crowd behind his last ride to Graceland.

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, 1856 – 1931, was an African-American surgeon who performed one of the first open heart surgeries, repairing a knife wound in a pericardium with sutures. The patient lived another 50 years. Williams graduated from the Chicago Medical College in 1883. Unable to practice in Chicago’s segregated hospitals, he opened the country’s first integrated hospital in 1891. He was the first black man to serve on the Illinois State Board of Health and as chief surgeon at Washington’s Freedmen’s Hospital. The only black founding member of the American College of Surgeons, and a founder in 1895 of the National Medical Association (the medical society founded for black doctors), he also served as an attending physician at Cook County Hospital.

Baseball and Boxing Greats

Considering one tomb that’s here, it seems appropriate now that Graceland Cemetery is a pleasant walk from Wrigley Field. The father of the National League is one of the figures from the world of sports who have their last time outs here, as well as two of boxing’s best-known names.

William Hulbert, 1832 – 1882, has a most appropriate memorial – a big, carved baseball. It marks the resting place of the man who founded the National League of Professional Baseball Clubs. Hulbert, a big fan of the game, became a stockholder in the Chicago White Stockings in 1870 and its president in 1875. The following year, he organized the National League with the 8 teams whose names are on the stone baseball. The White Stockings won the league’s first championship, and their descendants, the Cubs, play in Wrigley Field. Through an oversight, Hulbert wasn’t enshrined in Baseball’s Hall of Fame until 1995.

Jack Johnson, 1878 – 1946, knocked out Tommy Burns in Australia in 1908 and became the first black boxer to win the World Heavyweight championship. But other than a large stone with his last name on it, his Graceland grave is unmarked. That has caused some problems for fans who came looking to pay their respects after watching Ken Burns’ 2005 film “Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson” on public television. According to the family, plans are being made for a new memorial.

Robert Fitzsimmons, 1863 – 1917, a native of Cornwall, moved to New Zealand as a child, and representing that island nation, became boxing’s first three-division world champion – in the Middleweight, Light-Heavyweight and Heavyweight divisions, but not in that order. The Veterans Boxing Association of Illinois and other boxing fans replaced his original, misspelled headstone in 1973.

Merchants and Inventors

Sleepers, reapers, meatpackers, international reporting, a piano for every parlor – ideas and industry have always been a great team in Chicago. And Graceland is well represented with some of the biggest names in midwestern commerce.

Ernie "Mr. Cub" Banks, 1931 – 2015, Hall of Famer and prominent professional Major League baseball player Ernie Banks, or more notably referred to as "Mr. Cub", played for the Chicago Cubs from 1953 to 1971. Ernie Banks was the Cubs' first African-American player and one of the first Negro league players to join the MLB without first playing in the minor leagues. He is regarded as one of the greatest Cubs players of all time. In 2013, Ernie was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his contribution to sports.

Victor Lawson, 1850 - 1925

A Lorado Taft sculpture, “Crusader,” stands guard over the grave of newspaper publisher Victor Lawson, whose Chicago Daily News pioneered in sending reporters throughout the world for news. Lawson contributed anonymously to many of Chicago’s charitable causes, and even his grave is unmarked, except for the statue and the phrase, “Above all things truth beareth away the victory.” It refers to a story in the Book of Esdras, King James Bible Apocrypha, about a discussion of what is strongest.

George Pullman, 1831 - 1897

If you decide to sit and rest at the Pullman exedra (which means it has seats) you might well use the time to ponder what’s between you and George Pullman, the famous inventor of the sleeping car and the infamous landlord of his workers.

Solon Beman, who built Pullman’s feudally run town, designed the stately Corinthian column. But what’s underground is more interesting: Pullman’s coffin, covered in tarpaper and asphalt, is sunk in a concrete block the size of a room. On top of the block lie railroad ties and even more concrete. Why so secure? The family feared that Pullman’s angry workers, whose wages were cut while their rents remained the same, would resort to skullduggery at the gravesite.

William Kimball, 1828 – 1904, a traveling salesman from Maine, stopped in Chicago in 1857, and was so impressed with its vitality, he stayed and went into business as a wholesale dealer in pianos and organs. By 1881, he was successful enough to open an organ factory, and six years later, began making pianos, too.

Phillip Armour, 1832 – 1901, came to Chicago from Milwaukee to take over business enterprises from an ailing brother. Armour and his Chicago competitors Swift and Libby became the barons of the meatpacking industry, centered in the Union Stock Yards. It was said that the Chicago packers used all the pig but the squeal. The Armour plant closed in 1959, but his legacy remains. Armour helped build a technical school in 1893, the Armour Institute, which later merged into the Illinois Institute of Technology.

Cyrus McCormick, 1809 – 1884, is another man of means with a simple headstone at Graceland. Only 22 when he invented his world-changing reaper, he also pioneered the installment plan, allowing farmers to buy “on credit.” He built his first Chicago factory in 1847, and became one of the city’s largest employers as well as a millionaire.

Lucius Fisher, 1843 – 1916, fought for the Union during the Civil War and settled in Chicago afterward. He became president of the Union Bag & Paper Company, and founded the Exhaust Ventilator Company. His monument is actually an early columbarium – a vault to hold urns of cremated remains, a practice much more common today than a century ago.

John Glessner, 1843 – 1936, was, by all accounts, steady, dedicated to his work, devoted to his family and the finer things in life. He was Vice President of the very successful International Harvester Company, but you wouldn’t know it from the plain Glessner family plot at Graceland. Their Chicago home, however, is another story – Glessner left it for the people of Chicago as a museum. The Glessners were also instrumental in the founding of the Chicago Symphony, and supporters of the Art Institute, Rush Medical College and the Commercial Club.

WHO IN THE DICKENS IS THAT?

You might recognize some of these names, or you might not. But while each is vastly different from the next, they all add to Chicago’s fascinating history – and they each have Graceland Cemetery to keep their stories alive.

Eli Williams, 1799 – 1881, was one of the early settlers of Chicago, when the population numbered a mere 200. He ran a store, made money in real estate, built a hotel, became active in civic affairs, and died wealthy. Above him is a typical Victorian monument, a vine-covered woman holding a cross. On either side of him are his first and second wives.

John Kinzie, 1753 –1828, was the first permanent white settler of Chicago. The oldest gravestone in the cemetery, it marks the fourth and final resting place for a man who moved around in life, as well. A native of Quebec, he came here in 1804, settled in the homestead that Jean Baptiste du Sable had built, but was forced to leave for Michigan by the War of 1812. Originally interred in Fort Dearborn, he was moved to Chicago’s north side burial grounds, then to the lakefront cemetery, where the Lincoln Park project forced him to move one last time. Resting in peace, finally.

Augustus Dickens, 1827 – 1866, could have been a character in his much more famous brother’s writings. The younger brother of Charles Dickens, Augustus was well educated, but fated for as much obscurity as his brother was for fame. The facts of his life suggest that he emigrated to America to escape a wife, and, in fact, brought with him a different woman. He appeared in plays based on his brother’s writings, entertained Chicago’s leading citizens, failed in business, and until recently, his Graceland plot was unmarked. Dickensian, indeed.

Edith Rockefeller McCormick, 1872 – 1932, was a woman of great wealth – until the Depression. The daughter of John D. Rockefeller and daughter-in-law of Cyrus McCormick, Edith died virtually penniless, a result of the crash, lavish spending and unsound real estate investments.

Henry Brown Clark, 1801 – 1849, was another early settler of Chicago, and another example of someone who had a fortune and lost it. He came here in 1835, sought and found his fortune as a partner in a hardware firm and director of the Illinois State Bank. But his businesses failed in the Panic of 1837, and from then until his death of cholera, he supported his wife and six children by hunting and farming.

Mary Hastings Bradley, 1882 – 1976, was a prolific author of mysteries, travel books, and novels, most notably the Old Chicago series of historical novels. Frequently asked to lecture on her travels, she was inducted into the Society of Women Geographers, whose membership included, Amelia Earhart, Margaret Mead, and Eleanor Roosevelt. Mary was also one of the few female presidents of the Society of Midland Authors as well as an active clubwoman in Chicago.